Frank Lloyd Wright Houses - everything you need to know about the homes he designed

This list of Frank Lloyd Wright houses shows why they continue to be some of the most influential buildings in modern interior design

Frank Lloyd Wright houses are some of the most revered buildings in modern interior design. They have come to embody the mid-century movement, all interesting shapes, wide angles, clever use of timber and glass.

As an architect, Frank Lloyd Wright designed more than 1000 structures, bringing together a sense of peace, space and harmony with his homes' surrounding. Interestingly, reading through the list of Frank Lloyd Wright houses, it's clear many were not received well at the time they were made, and owners were often disgruntled at the finished results. Yet they've stood the test of time, with properties like Fallingwater reaching icon status for design lovers the world over. This list of the most notable of his buildings will provide insight into the thinking behind this prolific and hugely influential career.

Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio, completed 1889

At 22 years old, Frank Lloyd Wright designed a small two storey home for his family in Chicago’s leafy Oak Park, which was completed in 1899. It was the first house over which he had total creative control, having apprenticed at local architectural firm Adler & Sullivan before setting up his own practice in 1893.

The exterior of the house is in the Shingle style popular at the time, exhibiting the aesthetics’ wood cladding, an asymmetric façade, gambrel roof, and expansive veranda.

The interior hints at the liberated open space that would come to define Wright’s work; connected rooms flowing freely into each other. The architect sought to create an inspiring home for his family, dressing it with interesting, exotic and unique objects such as Oriental rugs, potted palms, sculptures, paintings and Japanese prints.

Wright’s home studio was to become the birth place of over 150 of his architectural projects, and where he would cement his reputation as one of the 20th century’s most formidable design minds. The architect continually revised and evolve the house, refining ideas that would reverberate into his work decades into the future.

The property was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972, declared a National Historic Landmark in 1976, and has been restored its 1909 appearance (the last year the Wrights lived there) by the Frank Lloyd Wright Preservation Trust.

Darwin D. Martin House, completed 1905

Designed and built by Frank Lloyd Wright from 1903 to 1905, the Darwin D. Martin House Complex in Buffalo, New York was built for local businessman Darwin D. Martin and his family.

The property is a series of connected buildings spanning the main residence, pergola, stable, the smaller Barton House for Martin’s sister and her husband, and a gardener's cottage. Wright also designed the interiors including lighting, rugs, furniture and textiles.

The complex demonstrates the Prairie School approach, which took influence from the landscape and wildlife of the United States’ Midwest prairie – juxtaposing the ornate Victorian architecture that dominated the late 19th century – focusing on purity of design, revelry of natural materials and seamless transitions between indoor and out. It was the first architectural style considered uniquely American. Typically, buildings were long and flat, with strong horizontal lines, overhanging eaves and covered porches, and open and flowing floorplans. Wright was the most notable of several architects from the era upholding the style, including his previous employer Louis Sullivan.

Referring to the Martin House as his ‘opus’, Wright is said to have kept its plans displayed near his drawing board for 50 years after its construction. The property was named a National Historic Landmark in 1986, however fell into disrepair and was partially demolished before being extensively reconstructed and restored in 2017.

The reception room of the David D Martin house

Frederick C. Robie House, completed 1910

Created for Frederick C. Robie and his young family in the South Side of Chicago and built between 1909-1911, the house came towards the end of Wright’s Prairie style exploration, its low walls, wrap around windows, and wide balconies and terrace encapsulating the aesthetic.

An open plan living and dining room is split into two segments, the interior space divided by a central fireplace and chimney with twelve glass doors providing a smooth transition between indoor and out.

The Robies lived in the property for only 14 months, and eventually it passed into the possession of the Chicago Theological Seminary as part of the University of Chicago campus. It served as a classroom, refectory, office, and a dormitory, when it suffered major internal damage; at one point a rocking chair handcrafted by Wright was salvaged from a rubbish heap by a janitor (who contacted the university years later to donate it for display).

A national outcry ensued after its demolition was announced in 1957, and Wright himself, aged 90, joined protests on site, commenting ‘It all goes to show the danger of entrusting anything spiritual to the clergy.’ The following year Robie House was bought by Wright’s friend New York real estate developer William Zeckendorf and donated to the University, which used it as a working building.

It was named a US National Historic Landmark in 1963, one of the 10 most significant structures of the 20th century by the American Institute of Architects in 1991, and its restoration to its 1910 appearance by the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust was completed in 2019.

Hollyhock House, completed 1921

Hollyhock House in Los Angeles’ East Hollywood was completed in 1921 for oil heiress Louise Aline Barnsdall as part of an art and theatre complex which was never finished.

In a dramatic departure from his earlier work, Wright drew on the visual influences of ancient Mexico, the residence one of the earliest examples of the Mayan Revival style which blossomed the 1920s and 1930s, of which Wright instrumental in leading.

The design drew on seventh-century Mayan temples, with inclined walls and colonnades mirroring buildings in the ancient city of Palenque. In response to Barnsdall’s brief for a ‘half house, half garden’, it is centred around a courtyard which opens onto a circular pool.

Inside, ground floor rooms lead outwards to external spaces, with a large decorative fireplace taking centre stage in the the living room, while the upper level accesses a roof terrace with views of the Hollywood Hills.

The name Hollyhock references Barnsdall’s favourite flower, and stylised representations of the plant decorate the project, cast in concrete on the exterior and across stained-glass windows, furniture, textiles and art.

In 1927 Barnsdall donated the house to the city of Los Angeles, and it was used as a creative space and venue before falling into disrepair, thanks in part to damage inflicted on it by the region’s predilection for heavy rainfall and earthquakes, which were not taken into consideration by Wright.

Now at the heart of the LA’s Barnsdall Art Park, it was fully restored in the early 2000s, designated a National Historic Landmark in 2007, opened to the public in 2015 (drawing crowds and queues through the night) and became Los Angeles’ first UNESCO World Heritage Site in in 2019.

The main reception room at Hollyhock House

Westhope, completed 1929

Constructed in Tulsa, Okalahoma in 1929, Westhope was designed as a home for Wright’s cousin (hence its alternative name Richard Lloyd Jones House).

It was said Lloyd Jones hated the building, expecting his cousin to create a structure that would fit the landscape, rather than the bold angular columns and walls of glass he was presented with.

The house was designed the ‘textile blocks’ Wright had created and was experimenting with at the time – against the wishes of his client – a unique concept involving stacking moulded patterned concrete cubes (Westhope’s patterns are Mayan-inspired). The result, was dampness, which the building suffered from all year round.

The interior focuses on open plan living, with public spaces on the sprawling ground floor, and private areas upstairs. The exterior holds a generous garage, garden room, workshop, pool, fountain, pond, gardens, four courtyards and a covered entrance.

The flat roof complied with the house’s theme of letting in water, immediately developing leaks. During a storm, Jones called Wright in a fit of frustration to say ‘Damn it, Frank! It’s leaking on my desk’ to which Wright replied ‘Richard, why don’t you move your desk?’ Jones’ wife Georgia commented; ‘This is what we get for leaving a work of art out in the rain.’

Fallingwater, completed 1935

Fallingwater is perhaps the most famous of the Frank Lloyd Wright houses, and lauded as the “best all-time work of American architecture” by the American Institute of Architects.

Built on the very top of a waterfall - hence its name - Fallingwater is in Pennsylvania’s Bear Run Nature Reserve. Water seems to flow out of it, the house both blending with and contrasting with its leafy environment. It has been hailed as redefining the relationship between humanity, architecture and the environment.

See our report on Fallingwater for more pictures and an indepth look.

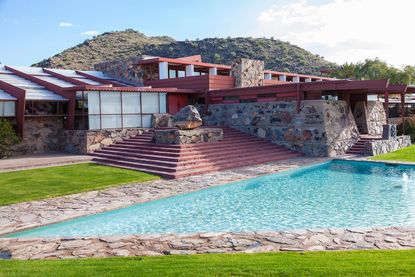

Taliesin West, completed 1937

In 1935 Wright was advised by his doctor to escape the bitter winters of his home Taliesin in Wisconsin, and so began the search for a plot of land in the sun. The result was Taliesin West in the Arizonan desert foothills, which was to become the architect’s winter residence and business headquarters as well as a live-in learning space for over 50 of his students.

After the purchase of several hundred acres of land (reportedly for $3.50 an acre) in 1937, up sprung a typically low-slung building constructed in the ‘desert masonry’ of cement-bound local rock, blending smoothly with the rich red landscape. By physically embedding the surrounds within the structure, Wright hoped to preserve and reflect the aesthetic of his new locale. Redwood beams added to the rich red palette, with the roof was made from translucent canvas to draw in natural light.

The complex continually evolved over the years. Wright spent every winter there until his death in 1959, and it is said upon his annual return he would stride around with a hammer making changes and relaying work orders to his apprentices, who followed behind with tools and wheelbarrows.

Taliesin West eventually included Wright's living and working space, residences for apprentices and staff, a workshop, drafting studio, dining facilities and three theatres for in-house entertainment. Each building is joined via a series of walkways, terraces, pools and gardens, and as usual Wright designed all of the furniture and decorations, the majority of which were made on site his students.

To this day the complex serves as the home of both the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation and Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture, with a small number of Fellows who lived and worked with Wright still to be found there.

Designated a National Historic Landmark in 1982, Taliesin West joined seven other Wright properties on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2019.

Sitting room at Taliesin West

Herbert and Katherine Jacobs First House, completed 1937

A challenge by his friend Herbert Jacobs to create a home for $5,000 lead to Herbert and Katherine Jacobs First House – nicknamed Jacobs I – constructed in 1937 in Madison, Wisconsin.

The house is hailed as Wright’s first and finest Usonian design, the architect using the term ‘Usonia’ – derived from ‘United States of North America’ – to describe his vision for affordable architecture that responded to the American landscape and eschewed entrenched European conventions, a style in which he would go on to build over 140 houses (including the Jacob’s Second House in 1948). Usonian buildings were of the earth, crafted in natural materials such as wood, stone and glass, without features such as porches, protruding chimneys or excessive shrubbery and open to the elements which were deemed ‘distracting’.

Entered by a hidden doorway leading from the cantilevered roof, Jacobs I features a wall of glass doors, the L-shaped open plan, living, dining and kitchen spaces fused and focused around a central fireplace.

The House is considered the purest and most renowned version of Usonian concepts – subsequent designs would become increasingly elaborate, losing the simple charm of the first iteration – and was to pave the way for the ranch style homes that colonised the post-war American suburbs.

Herbert and Katherine Jacobs Second House, completed 1948

A few years later, the Jacobs moved to a more rural part of Wisconsin and commissioned another Frank Lloyd Wright house.

Shaped around a soft curve, Wright termed the design as a 'Solar Hemicycle', meaning a segment of a circle.

The sitting room of Herbert and Katherine Jacobs Second House

Bachman-Wilson House, completed 1956

Designed for Gloria Bachman and her husband Abraham Wilson in 1954 and completed two years later, Bachman-Wilson House originally sat along the Millstone River in New Jersey. Bachman’s brother was an apprentice of Wright’s, and when the couple persuaded him to take on the commission, the architect replied ‘I suppose I am still here to try to do houses for such as you.’

The building exemplifies Wright's Usonian philosophy, the front façade made up of imposing concrete blocks trimmed with mahogany, with tall windows flooding the space with light, continuing Wright’s ongoing love affair with transparency and welcoming nature indoors. Unusually for a Usonian structure, the house has a second storey, although it is almost shrouded by the low, flat roof.

The open plan living room faces a dramatic wall of 10-foot-high glass, while cut wooden panels are decorated with Native American geometric motifs and stylised natural forms. A signature statement Wright fireplace seems squarely cut into the room’s core, surrounded by mid-century modern mahogany furniture to match the building’s frame.

The house was acquired by architects Sharon and Lawrence Tarantino in 1988, with the couple’s firm Tarantino Architects meticulously restoring it, receiving several awards for their work. Repeatedly in danger of flood damage, the building was sold to Arkansas’s Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in 2013 and relocated 1,235 miles to within its grounds.

Gordon House, completed 1963

Designed in 1957 for Evelyn and Conrad Gordon, great admirers of Wright’s, who ‘courted’ him until plans were drawn up, Gordon House is one of the last Usonian homes Wright created. Construction finished four years after the architect’s death in 1963, the project overseen by his former apprentice Burton Goodrich.

Built on the Gordon’s farm in Wilsonville, Oregon, the painted concrete block house’s floor-to-ceiling windows were positioned to take in views of the adjacent Willamette River and Mount Hood, the building exhibiting Wright’s classic design proportions and features, decorated with custom red cedar fretwork and blurring indoor with out once more. Typically, downstairs is an open plan zone with a generous terrace, while more private spaces with balconies are in the slim second storey.

After the Gordons' deaths in the late 1990s, new owners David and Carey Smith planned its demolition in favour of a more contemporary structure. This duly prompted outcry, with the 1989-founded The Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy stepping in and eventually given three months to dismantle and move the house 21 miles to its current home in the botanic Oregon Garden, where it’s now open to the public.

Frank Lloyd Wright furniture

The Peacock chair, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright

The furniture in Frank Lloyd Wright’s work was a key focus for the architect throughout his career, who stated in 1910 ‘it is quite impossible to consider the building one thing and its furnishings another...they are all mere structural details of its character and completeness’. His furniture pieces are defined by verticality, sharp lines, and simplicity and generally realised in rich woods, iconic examples of which are the Peacock chair, 1921, above, the rounded Barrell Chair of 1937, and the angular 1949 Taliesin Armchair, reissued by Cassina in 2018.

In the foreground of this image of the lounge area at Taliesin West are two original Taliesin armchair, since reissued by Cassina in 2018.

What is Frank Lloyd Wright architecture like?

Come across any Frank Lloyd Wright building, and you’ll know, be in it built in his early Prairie style, his later homages to Mayan design, the following Organic Architecture drawing from natural resources, or his final American-centric Usonian principles. Typified by their low bearing, slab-like flat roofs, great expanses of glass and exaltation of nature, the exteriors are decorated simply with subtle details – perhaps a concrete motif, geometric wood fretwork, or stylised stained-glass flower – while inside, rooms are minimal, flowing into one another, and blur the lines between indoor and out.

Frank Lloyd Wright facts

- Frank Lloyd Wright was born June 1867 in rural Wisconsin

- Frank Lloyd Wright studied civil engineering at the University of Wisconsin, going on to apprentice for the architecture firm Adler & Sullivan before opening his own practice in 1893.

- Wright was known for his brash personality, quoted as saying he demonstrated ‘honest arrogance and have seen no occasion to change’, and he had a similarly tumultuous personal life, marrying three times and fathering four sons and three daughters as well as adopting the daughter of his third wife.

- His boundary pushing work defined the global architectural landscape, and as such he has receive bounteous awards and world-wide recognition, including The Royal Institute of British Architects Gold Medal in 1941 and the AIA Gold Medal in 1949 from The American Institute of Architects, which also named him as ‘the greatest American architect of all time’ in 1991.

- In July 2019, eight of his creations were inscribed on the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites under the title ‘The 20th-century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright’. His work has been immortalised on postage stamps, with Lego sets, in song, and in numerous films, and work is on-going to protect his legacy.

How many buildings did Frank Lloyd Wright design

Frank Lloyd Wright designed more than 1,100 buildings, including these famous homes and a mix of other residential and commercial properties.

When did Frank Lloyd Wright die?

Frank Lloyd Wright died in April 1959 in Phoenix, Arizona, having lived life as a visionary architect, designer, writer, and teacher.

Frank Lloyd Wright

Be The First To Know

The Livingetc newsletter is your shortcut to the now and the next in home design. Subscribe today to receive a stunning free 200-page book of the best homes from around the world.

Amy Moorea Wong is a freelance interior design journalist with a decade of experience in contemporary print and digital editorial, previously News Editor at Livingetc. She writes on a broad range of modern design topics from news and interior zeitgeist to houses, architecture, travel and wider culture. She has a penchant for natural materials, surprising pops of colour and pattern and design with an eco edge.

-

The 12 Best Table Lamps for Reading —I'm a Certified Bookworm (and Shopping Expert)

The 12 Best Table Lamps for Reading —I'm a Certified Bookworm (and Shopping Expert)When it comes to table lamps for reading, I don't mess around. If you're the same, this edit is for YOU (and your books, or course — and good recommendations?)

By Brigid Kennedy Published

-

"It's Scandi Meets Californian-Cool" — The New Anthro Collab With Katie Hodges Hits Just the Right Style Note

"It's Scandi Meets Californian-Cool" — The New Anthro Collab With Katie Hodges Hits Just the Right Style NoteThe LA-based interior designer merges coastal cool with Scandinavian simplicity for a delightfully lived-in collection of elevated home furnishings

By Julia Demer Published

-

Art Deco design - a complete guide to making this nostalgic look work for modern homes

Art Deco design - a complete guide to making this nostalgic look work for modern homesJust as contemporary now as it was 100 years ago - Art Deco design is still infusing our interiors with it's joyful spirit. We breakdown how to get the look and make it work in your own home

By Rohini Wahi Published

-

A complete guide to Mid-century modern furniture – how to source the best pieces to nail the trend

A complete guide to Mid-century modern furniture – how to source the best pieces to nail the trendStylish, versatile and adored by many, we take you through everything you need to know about Mid-century modern furniture

By lauriedavidson Published

-

The Barcelona Chair: where to buy, how to style and all you need to know

The Barcelona Chair: where to buy, how to style and all you need to knowThe Barcelona Chair by Mies van der Rohe is one of the most famous pieces of modern design - here, we find out why

By Rory Robertson Last updated

-

The Egg Chair: where to buy, how to style and all you need to know

The Egg Chair: where to buy, how to style and all you need to knowThe Egg Chair by Arne Jacobsen is well loved and appears in many modern homes, and so we shine a spotlight on this mid-century hero

By Rory Robertson Published

-

Behind the Design: Frieda Gormley of House of Hackney on the story of how her classic Palmeral print came to be

Behind the Design: Frieda Gormley of House of Hackney on the story of how her classic Palmeral print came to beThe Palmeral design from House of Hackney launched a maximalist movement. Here's how it came to be

By Amy Moorea Wong Last updated

-

The Eames Lounge Chair: where to buy, how to style and all you need to know

The Eames Lounge Chair: where to buy, how to style and all you need to knowThe Eames Lounge chair design is a true mid-century masterpiece and interiors icon.We sit down and take a closer look at this cosseted design classic

By Rory Robertson Published

-

Anglepoise 1227 Desk Lamp: where to buy, how to style and all you need to know

Anglepoise 1227 Desk Lamp: where to buy, how to style and all you need to knowThe Anglepoise 1227 Desk lamp is an iconic piece of design, and so we shine a spotlight on this mid-century hero

By Rory Robertson Published

-

Farnsworth House - a look at Mies van der Rohe's mid-century icon

Farnsworth House - a look at Mies van der Rohe's mid-century iconTake an in depth tour of Farnsworth House, the home designed by Mies van der Rohe

By Amy Moorea Wong Last updated